Written by Marsha Seidelman, M.D.

October 23, 2018

You may have heard recently that lack of exercise is a greater risk factor for death than high blood pressure, high cholesterol or smoking. I was curious to see whether this was a sensational headline or if there was good data to back up the claim.

The article referred to in the popular press was posted on the open network of the Journal of the American Medical Association (jamanetwork.com), one of the major internal medicine publications. It was a review of over 120,000 consecutive patients undergoing treadmill testing from 1991 to 2014 at a tertiary center affiliated with The Cleveland Clinic. The patients had a significant incidence of heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, endstage renal disease and smoking, which are all risk factors for earlier death.

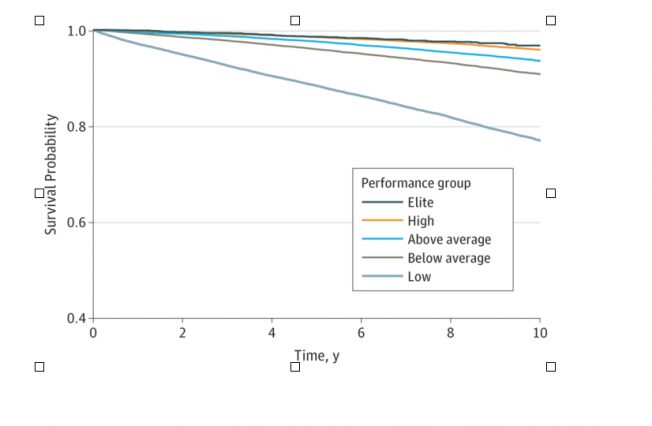

Their average age was 53 and slightly more male predominant. They were followed for 4-13 years. The risk of death was increased 5-fold in those with the lowest fitness level compared with the highest. What makes the data more credible is that there was a steady decrease in death rate as fitness increased along these 5 levels, as you can see in the diagram above. This makes it less likely to be just a random finding. All of the other risk factors, such as high blood pressure and smoking decreased as fitness increased. The one factor that did not follow that pattern is hyperlipidemia – the rate was a little higher in the most fit versus the least fit.

There has been some concern lately that there might be a higher risk of death in elite athletes, from such complications as an irregular heartbeat, calcium deposits in the coronary arteries, or unhealthy thickening of the heart wall, but that did not prove to be true here. In this study, they documented a benefit for elite athletes over the other high performance participants – i.e. in the top 2% of fitness even compared to the next best top 23%, with no observed upper limit of benefit. When they separated them out into age groups or risk factors, however, the benefit for the top 2% vs the next top 23% remained only for 70 years and older and for those with high blood pressure. So we don’t have to aim to be in the top 2%, but still, comparing all levels of fitness over the whole population, a high level of fitness is better than a lower level.

An important limitation of this study and many others, is that the association between a high level of fitness and a low death rate is just that – an association and does not prove causality. It could be that other factors that allow someone to exercise more are responsible for the improved survival. With that in mind, my own bias is that exercise improves outcomes in many ways – improved flexibility, decreased fall risk, increased independence, improved ability to experience the great outdoors and so on, and for all of these reasons whether it contributes to survival or not, it is still worthwhile. I would consider it as a quality of life issue.

When the authors compared the mortality of those with ‘below average fitness’ vs those with ‘above average’, there was a 40% increase in death rate for lower fitness. That is equivalent to the increased mortality due to having coronary artery disease, diabetes or being a smoker – hence the headlines you may have been seeing.

The key takeaway is that cardiorespiratory fitness is a modifiable indicator of long-term mortality – you are in control. Low fitness level is associated with a higher risk of death, as much or moreso than the traditional ones such as blood pressure, cholesterol and smoking. We’re all different and need to adjust our goals based on our limitations, but many people do have the time to exercise, and just choose not to or intend to but never get around to it. Walking, biking (indoors or outdoors), using an elliptical, or doing yoga – almost any physical activity – can increase your fitness. If you look at the graphs, you’ll see that each fitness group has a lower mortality rate than the group less fit than they are.

Exercise is more economical than medications Think of this article as a prescription to increase your activity, with the approval of your doctor, of course, if you have been relatively sedentary. If you’re interested in adding fitness to possibly decrease your risk of death, speak to your doctor, start slow, and find something you enjoy doing. An exercise program that feels like a chore won’t last long. Exercise time has to be scheduled and be a priority or it’s not going to happen! Put it at the top of your to-do list!

Whether it prolongs life as this article suggests, or not, as long as you proceed with logical precautions, it can’t hurt!

NOTE: Cardiorespiratory fitness in this article is determined by treadmill testing. The actual METs (metabolic equivalents achieved with treadmill exercise) were compared with the estimated maximum METs based on age. The individuals were ranked in fitness levels based on these ratios.

Reference:

Mandsager, K; Hard, S; Cremer,P. Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness with Long-term Mortality Among Adults Undergoing Exercise Treadmill Testing. 2018; 1(6):e183605.doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3605

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/article-abstract/2707428

Tags: exercise, fitness, mortality, survival benefit