Written by Thu Tran, MD,FACOG

August 16, 2019

This blog probably will be among the longest ones you have seen from me. I often warn my women friends whenever I write a long email, to tell them what I think about the week, from political news to social issues to all the “interesting” events happening to me that week. I advise them to empty their bladder, make a cup of coffee or tea and some snacks, and sit somewhere quiet in their homes so they can read the rest of my stories uninterrupted. You might want to do so before the next paragraph.

Like a typical physician, my life has been very hectic for decades. I work more than full time, if you count all the nights I stay up delivering babies followed by at least ten-hour days in the office seeing patients (in our group, we don’t take the day off after being on call). There was a time when a weekend call meant we were responsible for hospital work from Friday afternoon to Monday morning when the office resumed. We would drag ourselves home after office hours on Monday. We now are older and wiser; we divide weekend call into two blocks, from Friday to Sunday morning, and then another physician takes over from Sunday to Monday morning. Life is more breathable, but not as easy as someone who works only forty hours weekly and gets to sleep every night. I do love my job and consider obstetrics a privilege, as I get to witness the mysterious beginning of life. Like oncologists, we obstetricians are not immune from tragedies, but in my specialty, live births happen more than deaths resulting in what many consider a “happy field” of medical practice.

Since January, I have, on and off, experienced “epigastric discomfort,” a heavy sometimes painful sensation around the sternum, a little bone immediately below the chest. Eventually, it was present often enough that I decided to see my gastroenterologist. I was concerned that something bad was happening to me, as my maternal grandfather died of gastric cancer, and my mother had H. Pylori several times, a bacterial infection that can increase one’s risk for stomach or “gastric” cancer. After an unremarkable abdominal exam, my gastroenterologist recommended some antacids, while reminding me it was time for another colonoscopy .

Well, I got better and only had a bloating, uncomfortable sensation on and off. I drank less coffee, especially the strong Ethiopian coffee, and the upper abdominal pain and pressure seemed to subside. My busy life became even busier with all of the almost daily changes and updates in Electronic Medical Record (EMR) documentation requirements in both hospital and office, causing me to bring my laptop home every day to write longer and better notes, as I had minimal time to write notes in between seeing patients. How much we get reimbursed seems to correlate to how long and detailed our notes are. Our reimbursement from insurance companies is not as black and white as going to the mall to buy a pair of shoes.

Two weeks ago, after eating a small portion of “fizzy” guacamole, my stomach pain came back, this time sharp and persistent. I also had this bloating sensation as if something quite heavy was sitting directly on my stomach. Most often, I either ignore or have a high tolerance for pain, but this time, I called a radiologist friend who saw me a few hours later for an abdominal sonogram. She told me how sonography is not a good tool to pick up something bad in the stomach, but I went home happy that I did not have gallstones, or a mass in the area of the pancreas. I went to see my gastroenterologist two days later, who agreed it was time for an endoscopy, and promptly put me on her procedure schedule for the following Friday, a week after seeing me in her office.

In the recovery room, after the endoscopy, my physician informed me how she saw a 6 cm solid mass in my stomach. She worried that it could be leiomyosarcoma, an aggressive form of stomach cancer. As my husband walked me out to the parking lot of the surgical center, I turned to him and tried to be optimistic:

“I am an obstetrician, I know what 6 cm is like and I can tell you, the way she showed us the mass with her fingers, it might be only 4 cm!”

Why Gastric cancer? I said to myself. Did I once again inherit something “bad” from my maternal side? I had worked out intensively since I turned 30 years old, sometimes spending 14-16 hours a week in the gym, in my single days, doing all kind of intensive classes, lifting such heavy weights a personal trainer often told me how I had the fitness of the top 1% in my age group. Yet, I am a pre-diabetic with elevated cholesterol. My HDL, the good cholesterol, is quite high so it has protected me from having to take medications, but I know I cannot avoid medications forever because, as I age, my speed and strength inevitably will decrease. I knew my grandfather died of gastric cancer, but I also knew he had the unhealthy habits of heavy smoking, drinking, and eating the kind of diet in Asia that probably put him in at even higher risk for gastric cancer. I thought I did all the right things to avoid gastric cancer!

The weekend following the endoscopy, I was in panic mode. My physician friends, my dear lady docs friends, were equally upset. One put me in touch immediately with her staff to schedule a chest/abdomen/pelvis CT scan with contrast on Tuesday, since I was working on Monday and then on-call Monday night. My husband drove me to her Washington DC office for the study, where the newest CT machine was used. Sitting in the waiting room, I wondered what the radiologist would see. Why were my liver enzymes mildly elevated? No liver lesion was seen on the sonogram. Could it be that a liver lesion was just beginning to grow? Could my friend have missed a “tiny” liver metastasis? Recently, I noticed a normal workout left me more fatigued than usual. Could it be that there was something in my lung? How long has this gastric mass been growing in my stomach? How long had I ignored my symptoms? I was so anxious to have my CT scan completed that, according to my husband, I jumped up immediately when my name was called, and disappeared so quickly that he couldn’t even finish wishing me good luck and reassuring me that most likely all was fine.

The nurse who started my IV for the CT Scan told another nurse in the room how Toni Morrison the novelist had just died. On the way to the radiology center, I had read the news on Morrison’s death from my New York Times App. How blessed that Toni Morrison lived into her late 80s. How many women in the world have that privilege? Will I get to be that old?

The nurse was so apologetic about my gastric mass. She commented how hard it must have been for a physician to be “on the other side of medicine.”

“We are all mortals,” I said to myself. All physicians have to be, eventually, on “the other side of care.” Everyone seems to be shocked every time a physician faces serious illnesses, as if we are armed with knowledge and should be able to prevent all the horrible diseases from coming our way.

“I am actually lucky, considering my age,” I told my nice nurse, “I could have been the young mother who went shopping for school supplies for her children in the El Paso Walmart and got shot to death in the mass shooting yesterday.”

At least, even if this gastric mass turns out to be deadly, I thought to myself, I have time to fight and hope to be alive. That young mother did not have any chance against an AK-47 rifle in the hands of a hateful, violent man. She will never grow old enough to have cancer or heart disease. I was the more lucky one, the one with a gastric mass but with a fighting chance.

The radiologist who read my CT scan happily told me how my liver and lungs were clear, and my pelvic study was normal. He cautioned me, however, that CT scan is not the best tool to evaluate gastric masses. He could not tell if in fact it was a 6 cm mass.

That evening, I sent out a long email to the same group of Lady Docs friends to ask if anybody could connect me to a gastrointestinal (GI) surgeon at Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH). Within a few hours, a dear friend (a medical oncologist) told me she had reached out successfully to “the best surgeon” for me at JHH. She reassured me that she had sent many patients to him and they had been treated well and had achieved good results.

The surgeon met us two days later, in the busy Surgery clinic at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, in Baltimore. He was bright, kind and friendly. It was his operating day and he was in scrubs. I was grateful that he was able to squeeze me in between his surgical cases.

“We are the same age, but some of us manage to keep the color of their hair while mine are all gray!” He cheerfully greeted me.

“Well, that’s because some of us are vain, so we color our hair!” I cheerfully greeted him back.

Dr. Mark Duncan sat down with me and my husband David and patiently discussed the endoscopy photos on my cellphone, and the CT scan with contrast I received two days before. He reassured me that this “mass” probably was a Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor, or GIST, and not adenocarcinoma of the stomach, a highly aggressive cancer that often is seen in the Asian population. He was confident enough about the good prognosis of my gastric mass, that he said he would bet “a case of Coke,” not a can, but a whole case of Coke, that it would turn out to be “OK.” Why would a GI surgeon drink soda, I wondered? The CT scan showed my lung and liver were clear, he confirmed, with no enlargement of lymph nodes, so this mass had not spread anywhere. He believed it could be a “low grade” GIST that could be resected easily and with a minimally invasive approach. He shared that likely “fifteen years from now, you will look back and no longer worry about it!”

I did not know Dr. Duncan before, but I felt as if he was one of those who fights to get prisoners off death row! Didn’t he just take me off death row and back to a “nearly normal”prison?

I have at least fifteen years to live with gastric cancer? That sounds fantastic compared to glioblastoma like Senators Ted Kennedy and John McCain had, or Pancreatic cancer like many patients I know. Patients with these cancers vanish quickly, as if their cancers, once acknowledged, take it as permission to proliferate. The cancer cells were behind the curtain until making their grand entrance, to then slide across the stage like a fast dancer, dragging their hosts with them in a tug of war in front of the audience of families and friends. When it comes to cancers, we physicians know which ones we would “prefer” to have, and which ones we would “exchange” for a fatal heart attack instead of living with their horrendous treatments and poor survival rates.

My surgery was scheduled for a week later, ironically on my son’s birthday. I wrote to my friends jokingly how I had ruined my son’s birthday, and hoped he did not think I chose the date so I would not have to throw him a big birthday party.

I had everything planned out for my surgery date, how lucky that it would fall within my week of long-ago planned vacation! No patients had to be rescheduled. The surgeon advised taking two weeks off for recovery so, my front desk staff had to start immediately rescheduling many patients – quite a challenge since I have a three month long wait list! How terrible for the patients, I thought, to go through all the inconvenience of calling three months in advance for their appointments, only to now be rescheduled. I was still seeing my role as a physician and not a patient.

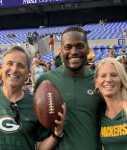

I started making plans for where my husband and son would stay, reminding David how the two of them were to see a football game in Baltimore between the Ravens and Green Bay Packers on Thursday evening. Our neighbor’s son-in-law is the Green Bay Packers’ Wide Receivers coach, whatever that might mean, since I do not watch football, but it was important that David and our son would not miss this game as the coach was expecting to take them on a private on-field tour. It would be convenient for them to go to the game and come back to the hotel nearby, now that I would be in the hospital and not home in Potomac. The timing of the surgery for Wednesday seemed to be perfect.

The day after I met Dr. Duncan, he called to inform me how he wanted me to have a repeat endoscopy, to “tattoo” the area where this mass was supposed to sit. He said that based on the CT, the radiologist at Johns Hopkins did not think the mass was even 5 cm. I was thrilled. The mass seemed to be smaller with time. I never believe in tattoos, as I always think it is such an unnecessary way to express oneself, given the risk of needle contamination. Why would one risk having Hepatitis C with tattoos? Having a mild case of needle phobia, it never makes sense to me that people have tattoos. But then, my internal tattoo probably would be different. How do you tattoo an internal tumor?

Dr. Duncan told me how my endoscopy was to take place… the day after he called me, exactly a week after I was diagnosed with a gastric mass. I was grateful for the speed of my workup, although I imagined the cancer cells could not have multiplied that quickly in a week. After all, I might have had this mass since January; a week would not change my prognosis.

We returned to Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center last Friday for the second endoscopy. I could not believe my stroke of “luck.” My whole life of excellent health until now, when I ended up under anesthesia twice within seven days, and having tolerated intravenous placement three times in three different institutions. All the nurses complimented my “big veins,“ which made their job much easier. Weight training and aerobic exercise have benefits other than strength and cardiovascular protection; they make you better patients, with easier venous access!

I love having Propofol for surgery. My mind was lucid and I had no memory impairment afterward. I understood and remembered (I think!!) everything my physicians told me. The young anesthesiologist at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center informed me and my husband that the area in focus looked “interesting.” She believed it was not necessarily a cancerous mass, but an ulcer with some swelling and redness along with some “stomach folds.” She had called the surgeon, who was on his way to Ireland to run a half marathon with his son and, together, they decided I should take some strong antacids and have another endoscopy in ten weeks. She also informed me how the CT scan’s final reading was that it showed no mass. Johns Hopkins radiologists reviewed the CT scan and agreed with my friend that there was no gastric mass.

Not only I was taken off death row and sent back to prison, I am now on parole, for at least ten weeks. My side of the bargain is to take this antacid medication once daily to see if this “ulcer” will improve its “interesting” appearance. When it comes to illnesses or medical conditions, I don’t think too many of us would want to have something ‘interesting” growing internally.

On my son’s birthday, I was NOT admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital for abdominal surgery. I did NOT have to receive general anesthesia for the third time in a week and a half. My veins were NOT poked. I was NOT put on clear liquids the day before and was NOT put on “Nothing By Mouth” or NPO status after midnight. Instead, I woke up and went to the gym for a bootcamp class called “INTENSITY,’ now that I no longer worried that my intense moves would rupture “the gastric mass” and send its cancer cells everywhere in my abdomen. I lifted heavy weights at each station intentionally, knowing that my arms and legs were still real. I was not a ghost; I was not in the hospital.

In the afternoon, when my case would have been started, I went outside to plant some lavender, and watched my rare succulent flowers in full bloom. I wrote to my friends a few days before, how the poor street vendor in a Vietnamese mall in Fairfax, Virginia, instructed that I water it sparingly, once every few weeks. Overwatering and it will die, she advised me. For years, this rare succulent bloomed only once. I decided to put it outside this spring for some sun, subjecting it to so much rain and numerous storms. Like a miracle, the succulent plant started budding a day or two before my first endoscopy with three huge flower buds. Within a week, two out of three flowers opened widely, a lucky and good Darwinian sign, I wrote to my friends. I saw life instead of death, after all that pouring rain.

The evening when I would’ve been recovering from my surgery and drinking clear liquids, we took our son out for his birthday and had a great sushi dinner. We went to the movies and were the only three in a big theater in Rockville, watching “The Farewell,” a wonderful movie and true story about a Chinese family dealing with an elderly relative with end stage lung cancer. Now that I no longer had fear for having cancer and dying from it, I found enough courage to watch a movie about someone else dying of cancer. In order to gather the family members who had migrated away from the city in China (to the United States, to Japan) for a final visit with their mother/grandmother, they agreed that all would return to China to attend and celebrate the wedding of the grandson, without mentioning anything about the grandmother’s illness. As in the usual Asian culture, the relatives and physicians of this woman tried to hide from her that she had terminal cancer. Her son explained to his protesting “Americanized” niece who adored her grandmother, why they had to hide this fact from her. He explained that the Chinese believe the cancer often is not the cause of a patient’s death, it is the patient’s mind that ends up killing her. He also explained that in the Asian culture, the burden of the cancer diagnosis and illness should be carried by the family, not the grandmother (the patient). The family participated in this wedding and celebration of family love and relationships because one’s life and death, in the Chinese culture, is not considered an independent entity. A person’s life is “a part of a whole.”

I was too “Americanized” while facing my potential cancer. I reached out from the beginning to my village of good friends, and they responded immediately with deep love and concern. There were plans to bring food for us after surgery, flavorful nutritious broth made for a foodie like me, instead of leaving me to drink hospital bouillon as my clear liquid. Two friends came to my house a few days before surgery, bringing me a new, luxurious and cozy bath robe and UGG slippers, presents from the group to keep me comfortable in the hospital. Another friend, an ENT surgeon who was under treatment a few years ago for ovarian cancer, advised me to wear scrubs in recovery. Scrubs were the most comfortable clothes for her after surgery.

“Forget about Pajamas, just wear scrubs!” she said. Physicians and surgeons will always look like they are at work.

There were floods of email chains, with more than forty people on the threads, that could have been turned into a book about life and death and illnesses. There were multiple opinions on different aspects of diagnosis, treatment interventions and where to go for surgery. Should a “PET” scan or MRI be performed? Should I be scheduled immediately for an endoscopic ultrasound? What would be the “differential diagnosis” for my elevated liver function tests if my liver indeed was clear from this mass? Which hospital in our area is best for GI cancers?

There were “too many chefs in the kitchen,” my husband commented “it becomes overly confusing with all the varying information and opinions.”

When it comes to something that can potentially end my life sooner than expected, it might not be a bad idea to have too many chefs in the kitchen, I told my husband. It would be like preparing for a banquet and not just a dish. Maybe one chef would recognize the difference between using cilantro instead of Italian parsley for a recipe, a subtle change that would make the dish more perfect. It was the second endoscopy that saved me from having surgery. Many times, patients need these “second looks” to avoid unnecessary surgeries and their potential long lasting complications.

I never had to finish writing down the list of charities to which my husband was to donate on my behalf.

“Don’t forget Doctors Without Borders!” I told him the day after the gastric mass was found.

All ended well. I most likely do not have gastric cancer. This “interesting looking” area most probably is, like the surgeon and the GI physician at Johns Hopkins said, a chronic ulcer. The madness of the last two weeks was just a “shake up.” Looking back, it was a scary shake up with many learning lessons. I learned to fear like a patient, not like a physician for her patients who face newly diagnosed cancer. I now understand the anxiety when patients are alone in the CT scan machines, alone while waiting for their test results, alone when the propofol is about to ease them into their temporary sleep, when sounds in the OR room suddenly become muffled, as if they are about to bid farewell to the living world. I now understand the urgency of living when we learn we are facing a serious illness, and the uncertainties about our past and future life. Did I work too hard, missing a chance to live a more well-rounded life? Should I stop working now, or how might I restructure my life? What else out there that I would like to explore on this day, the first day of the rest of my life? A friend pointed out how intense I have been living, that I never seem to have “downtime.” A big junk of my downtime, she stated, was spent in the gym and not just “real down time.”

For all the confusion and fear about my new medical condition, I learned how much I have been loved by my friends and family. The open affection through the email chains reminded me of a story in the New York Times about Mr. John Shields, a gentleman in British Columbia with an incurable disease who, from his hospice bed, organized an Irish wake for himself. His families and friends all gathered at a local restaurant where he had his last supper of what he used to enjoy when he was a young Catholic priest – chicken legs and gravy. It was a big celebration of life, with alcohol, music and great food. His families and friends came to tell him how much they cared about him and what his life meant to them. The following day, Mr. Shields was given a lethal injection at home, in his favorite spot, by his physician, as he did not change his mind about dying on his own terms. He had a fabulous and unique life, and experienced, during his live wake, the outpouring love from those important to him. Wouldn’t we all want such fabulous ending to a life well lived?

Unlike Mr. John Shields, I do not have an incurable disease, or, not yet. I had a brief experience of what it would be like to be a patient with a serious medical condition. I will go back to work next week, and have been back to my routines. However, I might be a bit wiser. Instead of staying in the gym for two consecutive classes yesterday, I decided to go home and spent that hour weeding my much neglected vegetable garden. I am throwing a summer picnic for my father and siblings this weekend. I started reading one of the two novels sent by my friend and primary care physician, who advised me not to read all sad and serious books often picked for our Lady Docs bookclub. We always try to solve or discuss the serious problems in the world, which often leave us feeling solemn. Maybe once in a while, I need to read a fun fiction novel with a happy ending. My gastric mass was probably a fiction with happy ending. I will keep my fingers crossed for the next ten weeks.

“I’d lose everything so I can sing

Hallelujah, I’m free

(I’m free, I’m free)

I have lived my life so perfectly

Kept to all my lines so carefully

I’d lose everything so I can sing

Hallelujah, I’m free

I’m free, I’m free

I’m free, I’m free, I’m free

Hallelujah, I’m free”

——Free, by Broods

Tags: cancer, gastric cancer, stomach cancer